FORMS OF LIGHT

No one is so completely disenchanted with the world, or knows it so thoroughly, or is so utterly disgusted with it, that when it begins to smile upon him he does not become partially reconciled to it.

- Giacomo Leopardi

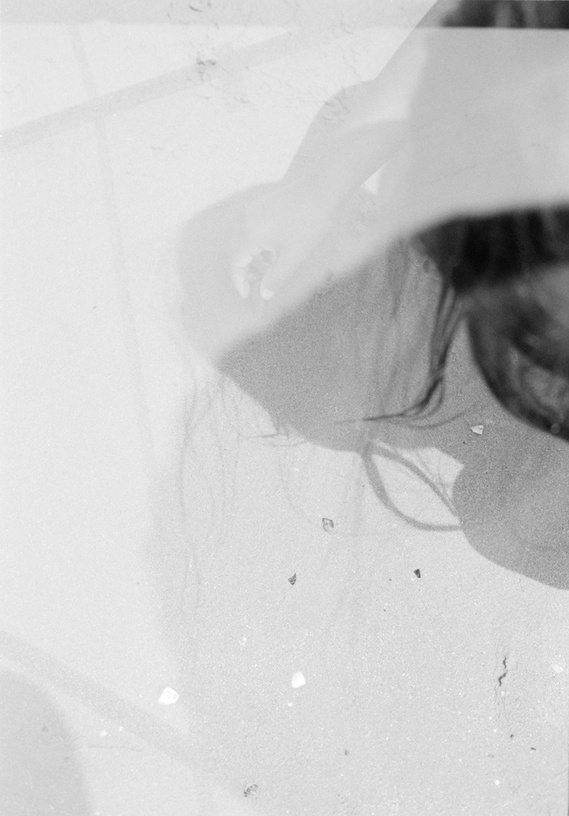

A young girl squatting in a perfect concave curve on the beach, her dark hair bleached out by burning sunshine and the double exposure of an adjacent negative. Filigree grids of leaves resembling feminine laces thrown onto shades of white, milky as alabaster. Stark daylight erasing the distinction between ocean and sky, turning the charcoal black breakwater into a sculptural monochrome. Massimo Leardini's pure organic-poetic form offers the radiance of light in alignment with its opposite, negotiating between the opaque and what is clearly visible. An epiphany of non-events - a clothesline transformed into ghostlike shadows on the concrete below - that create a heightening of our attention with their keenly tuned modulations of light; powdery as marble or translucent as soothing water juxtaposed against volcanic tones of black.

Less images of visual phenomena than of perception itself, Catarsi is a world beyond the depicted. And yet, the images' dreamlike, warm whites and harmonious structures of glowing greys are firmly rooted in an underexposed narrative extracted from the realms of the photographer's seaside hometown of Cattolica, Italy, where he first started taking pictures of bathers for the local municipality during his teenage years. Ornamental foliage could be of any fine symphony of summer leaves, but not for Leardini. A personal horizon of infinite Adriatic sea and sunlight play a cameo role here. Catarsi is a journey home, perceived from the freedom of seeing it from far away up close.

Regionalism has long been an important factor in the history of Italian photography, and the Adriatic coastline encompasses the innovative post-war movements La Bussola and La Misa both of which were founded by Giuseppe Cavalli and included Mario Giacomelli amongst their most celebrated practitioners. These photographers pursued a simple, quiet aesthetic, favouring formalistic experimentation gradually blending with Italian Neorealism and social documentary practices that were developing elsewhere in Europe and the US. Opposed to the overblown didactic imagery of the Fascist era, Cavalli subscribed to the principle that «in art the subject has no importance at all.» Rather, each object in his frame was a vehicle for the element he really wanted to capture – light. In a part of Italy where old ways were passed on from generation to generation, this expressive legacy can be seen as a humanist backdrop to the Catarsi series' compassion for the grain of a landscape - its textures, shapes and tones celebrated with the temperament of a contemporary classic.

The pictorialism of Leardini's imagery also stems from photography as the successor to fine art of the past. Or as the La Bussola group asserted: "We believe in photography as art. […] It is equally possible to be poets with the lens as with the brush, the chisel or the pen." Leardini's is the camera of the magical realist whose images can be a visual parameter of the most subtle nuances of human experience; its black and white hues approaching the alternatives of hope and despair to which mankind is forever subjected, as Robert Frank observed. In Catarsi, Leardini employs colour with a carefully muted palette, reminiscent of the Kodachrome tints of romantic spirits before him. The emphasis on surface and spatial ambiguity creates abstract allure, with light taking on an intimate, tactile presence.

In a digital era, Leardini remains true to the use of photographic film and the alchemy of the laboratory. The ontology of the negative shares a particular relationship with the past by freezing the photographed moment, forever gone, in a myriad of different ways, to denote photography's spectral conjuring of death-in-life. Particular, however, to Catarsi is how the images arrest the flow of time with a lighter sensitivity. Traces of sunlight across velvet strands of a young boy's hair rejoice in a paradoxical sense of weightlessness in terms of time. The ephemeral and the eternal coexist in surfaces of rock and gravel, and in the way the even lighting tests the limits of what the eye will grasp - as for example in the backlit features of a Catholic relic – opening up a space between times.

Leardini's tender, elegiac series delights in the present tense, as if asking how one can give visual equivalents of life - to use an essential concept of Alfred Stieglitz', who named his photographic series of clouds Equivalents. The answer of course resides in the singularity of photography as a medium. Exquisite handling of effervescent lighting conditions reveal a poetic sensibility in which man and family become traces in a larger composition. As in the literature of another poet born on the Adriatic shores, Giacomo Leopardi, elements of nature create a window to ambiguously unanswered metaphysical questions. In the photographer's abstraction of a particular Italian landscape into a personal aesthetics, there is always a fine balance between transcendence and the profane. However, the optics at play, integrating personal and collective memory, seize nothing less than the luminous allegria of life.

In a discussion of his work in 1973, Italian film director Roberto Rossellini claimed: "I don’t want to seduce, I don’t want to persuade. I want to offer." A parallel open-ended set of readings may apply to the relationship with the sensuous shared in Leardini's work. Monochromatic images of unpopulated beachscapes lost in dazzling Mediterranean off-season light open onto the precariousness of everything with the beauty of the forever transitory. In what pictorialist master Julia Margaret Cameron termed the "effect of full sun light", the eye finds ease. -Torunn Liven - Oslo, 2015